A few weeks ago I wrote a review of The Good Companions by JB Priestley in which I mentioned the use of spelt-out accents and West Riding dialect, which I saw as necessary for the character. Writing that review made me realise my perspective on dialect and accents in novels has at least partially changed since I last substantially wrote on the topic in 2009 and referred to ‘the bizarre and unnecessary rendering of accents into written form’, so here are some updated thoughts. I’d also be interested to know what you think.

What am I on about?

By ‘accent’ I mean how someone pronounces standard English, and I’m using ‘dialect’ to mean words that aren’t in standard English but are in regional use. These are probably not the same as the technical linguistic definitions but I only studied this at GCSE, which was 30 years ago and all I remember about it is analysing a Boddingtons beer advert where they looked posh but sounded Manc.

I took against dialect in books at an early age. In 2013 I mentioned in a post about reading Yorkshire-set books, “As a child I had a couple of bad experiences of Yorkshire-related works, but thankfully it didn’t put me off. I remember The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett being recommended as it was set in Yorkshire but I can’t remember if I got to the end. I seem to recall (bearing in mind I haven’t touched it in twenty-five years or more) Yorkshire dialect written in a way that almost seemed like a caricature, and only for characters you were supposed to look down on” — specifically the housemaid, as I recall.

A glance through the author’s biography on Wikipedia suggests she wasn’t writing the maid’s speech in a familiar voice, being Lancashire-born and US-raised. In fact it sounds like she never so much as visited the North York Moors. While I am very much not one of those people who thinks authors should stick to their own background, culture or country, it does go to show how jarring it can be if it’s not done well1.

Two points arise from this: whether the voice (accent and dialect) you’re writing is your own or at least one you’re familiar with; and how it’s supposed to make a reader view the character. I’ll add a third — will anyone understand you? — and that just about covers everything I want to say today. Now read on…

Why bother?

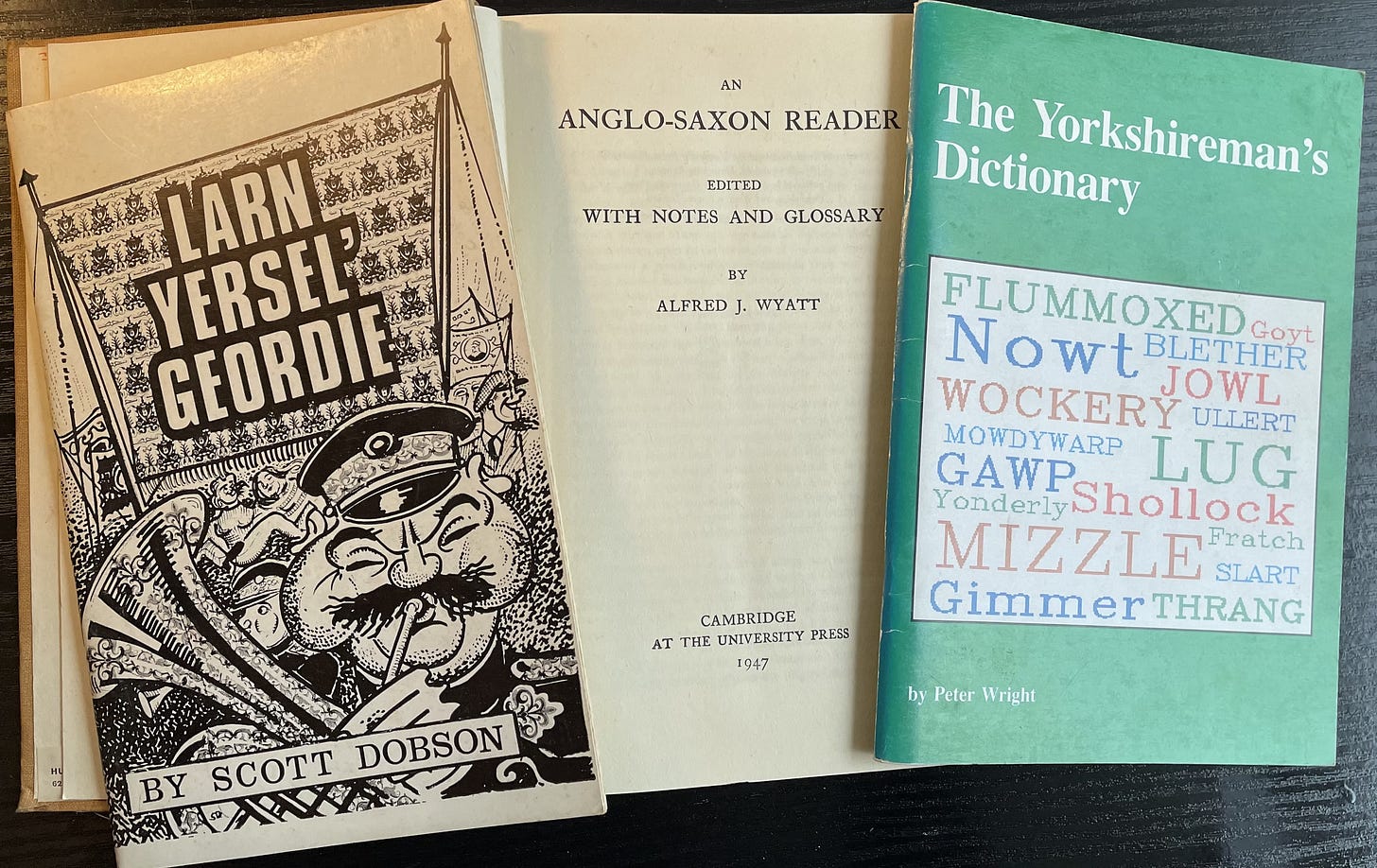

My (Geordie2) other half pointed out to me that if ‘I'm going home’ was written down, a Geordie would probably read those exact words out in standard English with an accent, whereas if they were to announce in person that they were going home, they may well use a phrase that I would have to render for the well-spoken Yorkshireman3 as gan'n hyem which, like a lot of Geordie dialect, is actually Anglo Saxon but that’s a different story.

Similarly I would read out ‘down by the shed’ as you might expect, but if I was to tell you where I’d left the wheelbarrow I’d say something you might spell as ‘down bi’t’ shed’ where that apostrophe t after the bi (same vowel sound as in quick) is doing some very heavy lifting as a swallowed ‘the’ which is definitely there, but bears no resemblance to its usual spelling (t’shed). My spoken version is shorter and more staccato than the standard English one so if that’s important in the context, you might think the standard English is as much a misrepresentation as it was in the Geordie example above.

When you’re writing dialogue (or a first-person narrative) you might strive for authenticity but you would never put in all of the hesitations, false starts and backtracks that you would find in an actual transcript. It would be tedious, hard to read, and wouldn’t help the reader focus on what was important. How about word order, word choice, and pronunciation?

The order of words changes the rhythm of the sentence. Someone saying they can’t find their keys, and their spouse replying ‘Can’t you?’ is different from ‘Can you not?’ even though it means exactly the same thing. Typical word order can be different in different areas, so it’s a subtle way of imparting accent or background without changing the words themselves.

In the first Pirates of the Caribbean film there’s a line something like, ‘I’m disinclined to acquiesce to your request. That means no’. Think about the difference between saying that long lyrical phrase or just saying ‘no’; it’s a lot harder to shout the phrase in a tense situation to convey at speed your disinclination to acquiesce, so it works best at leisure. A string of long words sounds funny coming from a pirate, who you might expect to be a rough and uneducated sort, so you’ve got humour whether you meant to or not.

Word choice matters, and as readers we instinctively spot where something seems out of place — too long-winded or posh or stilted — and it feels more natural to have a certain amount of colloquialisms, slang or jargon. Where does the regional element come in?

In my experience, Geordie women in conversation can’t go five minutes without saying ‘Ee!’ to convey surprise, approval, disapproval, disappointment, shock, commiseration, excitement, or the feeling of being mildly scandalised by imparted gossip4. To give a flavour for those who don’t know, and to make it feel more obviously Geordie for those who do, I’d want to add an ‘Ee!’ now and then if I was writing, say, a woman in her fifties from Wallsend. The longer it’s drawn out, the stronger the feeling, so if I wanted to capture an authentic-sounding voice in writing I’d probably want to spell some of them with seven Es to show how long they were and thus how shocked, excited etc the character was, and this is beginning to lead us down the road of spelling out accents.

You can only go so far with standard English plus the odd easy-to-recognise deviation like ain’t or yeah. Depending on how far from standard English your character is, you might need to go much further. As I said back in 2009, ‘a thicker accent and a lot more dialect gets used in my head than would ever emerge from my over-educated mouth these days’ so I don’t know how often I use forms of thee, thy and thou out loud (never at the day-job) but it’s not unheard of in 21st-century Yorkshire. That’s not something I could convey using standard English.

Neither does ‘she was only a child’ give quite the same impression as ‘she was no’but a bairn’. That last phrase is from an unfinished story of mine where a lady in her eighties hears that Princess Margaret (barely in her seventies) has died. She would never say Princess Margaret was a child, but ‘she was no’but a bairn’ is a perfectly reasonable, mildly humorous comment that tells us how much younger than her she thinks of the dead royal as being.

Familiar noises

Having noted that using dialect or trying to spell an accent phonetically can be excruciating when done with a tin ear, and although in the meantime I’d run across renderings I didn’t mind too much, I think I only realised how well it can work and what it can add when I read The Good Companions. The difference is perhaps a question of familiarity. JB Priestley, being from Bradford, would have grown up surrounded by versions of the voice he was trying to convey for Mr Oakroyd. Priestley’s dad was a teacher so I don’t imagine they spoke like that at home, but his mother had been a mill girl so he must have had some relations who did. I’ll come back to that class difference in a bit.

Although I remember Half Blood Blues by Esi Edugyan having some non-standard spellings for American characters, I mainly know about Yorkshire and Scottish ones (I am aware there are a multitude of accents across Scotland and its islands — here I mean all of them, not some theoretical single accent labelled ‘Scottish’). I mainly read fiction by British authors, and they seem to be the accents that get spelt-out the most often; maybe I should say northern English and Scottish, because it’s probably not just Yorkshire5.

Back in 2009 when I was moaning about the mangled English of Andy Dalziel in an otherwise enjoyable Dalziel and Pascoe novel by Reginald Hill (from northern England himself, though not Yorkshire), I said:

a Welsh character was written in standard English but we were told she had a distinctive Celtic lilt, whereas a Scot was given similar treatment to Dalziel himself. Is that just because we're used to northern accents being rendered this way, whereas there are no standard spellings for the pronunciation of English in South Wales?

Maybe there are standard spellings, but Reginald Hill didn’t know them? You can only use words you know about, and you’ve got to have a reasonable expectation your readers will know them too.

Say what?

JB Priestley was effectively writing Mr Oakroyd for me to read: I grew up in the same area, as did my parents, grandparents, and most of my great-grandparents6. I didn’t have to ‘put an accent on’ and there was only one dialect phrase I didn’t understand (not bad going, considering it’s from nearly a hundred years ago). He was also writing the other spelt-out accents for me, in the sense that he’ll have had in mind the vowels of the well-spoken Yorkshireman as his starting point, being an archetypal one himself.

Back in 2009 I said that my natural baseline for writing is well-spoken Yorkshire, by which I meant ‘Noticeably northern, but consciously or unconsciously modified by the character into a form less likely to make other people assume they're stupid’. This comes from being cautioned at school never to use dialect in public in case people thought we were thick. I will come back to this later, though I’m trying very hard not to start class warfare in this post…

Writing phonetically means you have a particular reader’s accent in mind. If you write ‘luv’ to denote a northern ‘love’, I’m going to pronounce them both the same, so whose accent were you trying to modify by writing it like that? And are you sure you’re going to prompt the same sound in the reader’s head as you can hear in yours? Fifteen years ago I used this example, having read a fair few Ben Elton novels in my teens and twenties:

Ben Elton's particularly fond of denoting differences in background…by the spelling of a popular swear-word... So northerners say "fook", southerners say "fack", and posh southerners say "fark"…Is Ben Elton assuming that his readership will all have middle-class middle-England non-accents to start with? Or that we might need a bit of a hint on how people speak, beyond "she was from Manchester"?

…Even among northerners there's no uniformity in pronunciation of that double-o; some Lancashire accents rhyme "look" with how I'd say "Luke", whereas [my other half] and I rhyme it with "luck", for me, "book" and "cook" have the same sound as "look", but [my other half] rhymes "book" with something closer to "Luke" than "look" while not being either.

The key thing to remember is that you’re trying to be understood by a reader. There’s a danger that by trying to spell out an accent or use dialect words that many readers won’t recognise, you’re making it harder for everyone. Here’s another couple of excerpts from my 2009 posts:

Reginald Hill has his Yorkshire detective Dalziel saying 'thyself' from time to time, but I'm willing to bet that that character would pronounce it, in his own phonetic rendering, as 'thissenn' (that's how I say it), so why the standard English spelling? The assumption here would be that most people don't use the word so wouldn't recognise it in disguise and wouldn't understand what he was getting at. At least there was a standard English spelling to fall back on; most dialect words are rarely written down because (unless you're north of the border, where Scots is championed as a separate language) we're all taught to use standard English when we write, no matter what words we use when we speak…

…I first encountered this as a child, reading the James Herriot vet books after I'd seen some episodes of All Creatures Great and Small on TV. I read the books in a Yorkshire accent, at that age I doubt I could have read them in any other, but there were always speeches I couldn't understand, strange spellings and a confusing trait of putting t' before most words. When it was eventually pointed out to me that this t' was supposed to represent the swallowed "the" that I'd naturally been using since I first learned to speak, I was puzzled: reading "t'kitchen" made me say something in my head that sounded like "to kitchen", hence the confusion. And I wasn't convinced anyone from outside Yorkshire would say it right from that rendering, as it's a hard one to learn. Why not just write "the kitchen", so everyone understands what's meant, and if they want to (or have to) say it in the Yorkshire accent they know the character has, that's an added bonus?

It can be excluding when you don’t understand it. I remember the film Trainspotting came out when I was in sixth form, and one of my friends bought the book by Irvine Welsh. I looked at the first page and couldn’t understand a word. No doubt the characters could best be portrayed that way, and Welsh was using his own or a very familiar voice, but I dare say if The Good Companions had Mr Oakroyd from anywhere else in the country, I wouldn’t have been as happy about his highly authentic speech and probably wouldn’t have enjoyed the book half as much.

Undesirables

This post is getting pretty long so those of you who prefer the quiet life will be pleased to know I haven’t left much room for exploring class and accent. Regional accent and class go broadly hand in hand (the stronger the one, the lower the other is assumed to be, at least in England) and so it’s inevitable that spelt-out accents or use of dialect goes with the working class characters.

Andy Dalziel in the Reginald Hill detective novels is a clever and insightful senior policeman but he’s also rough, crude and never went to university. In contrast to the university-educated, well-spoken, polite Peter Pascoe who always speaks in standard English, Dalziel is as thoroughly working-class Yorkshire as Hill can make him through his speech patterns. People in the novels underestimate him or make assumptions about him because of the way he speaks and behaves, as no doubt various readers do too, but unlike the maid in The Secret Garden, we’re not supposed to look down on him.

There’s a John Wyndham novel (Plan For Chaos) in which he had to invent a strange peripatetic childhood for his main character because he tried to make him an American and couldn’t do the dialogue; it becomes a kind of running gag that he sounds like he’s trying to learn American

i.e. from Tyneside in north east England

We’ll get into whose accent you’re spelling for in a while

Maybe it’s only my other half’s extended family, but I don’t think so

Lee Stuart Evans uses it for a Nottinghamshire accent in his first novel, Words Best Sung and Nottinghamshire rubs up against Yorkshire so we’ll call it northern for now. As with JB Priestley he’s rendering familiar voices from his own upbringing.

26 years with a Geordie other half has taken its toll though — a few weeks ago someone who’s originally from Newcastle asked me what part of the north-east I was from. In time, I may get over it.

This is so interesting! For what it's worth, I didn't read the accents and dialect in The Secret Garden as meant to make us look down on the characters (and it certainly didn’t do that for me as a child reading it far away in the US). The characters who speak ”broad Yorkshire” are the most adult and sane people in the novel, including the children (the maid, Martha, who is a child herself, and her younger brother). But to your point: I have huge amounts of dialog from the book in my head still, spelling and all, but to this day I have no idea of how they are actually supposed to sound!

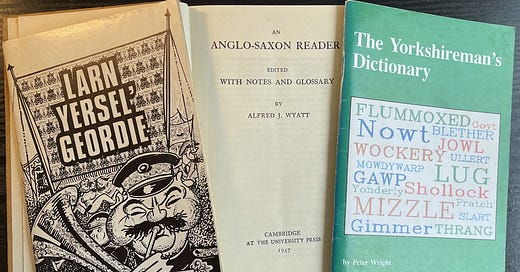

Much enjoyed reading this Jacqueline. I write what I call my 'Meanders' of my life back in the northeast having left it some 50 years ago as an economic migrant. One or two of those pieces have covered accent/dialect and it's Angle origins (the Saxons were all southern based). I recall buying Larn yersel Geordie for my first wife (born in Kent) back in 1975 to help her with translation. Interestingly the Kent miners I met used several Geordie words such as Marra and Kidda (although strictly speaking they are more Pitmatic than Geordie) that I assume came from past generation northeasten émigrés who fancied warmer southern climes. Anyway, great piece and gan canny 😉