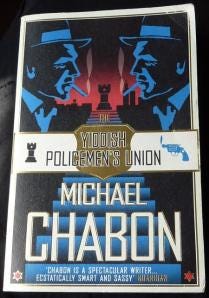

The Yiddish Policemen's Union by Michael Chabon

Imagine a world where Israel didn't become a state in 1948, and where the largest Jewish community is a North American backwater tolerated (mostly) by the local Tlingit people on the understanding that it's purely a temporary measure. Now imagine an unidentified Jewish junkie is found dead in his room in the same fleapit hotel that the area's premier homicide detective currently calls home, on the eve of mass eviction. You have the beginnings of The Yiddish Policemen's Union, an unusual novel that I enjoyed a great deal.

Sitka, in Michael Chabon's world, is a small Yiddish-speaking homeland in the heart of Alaska on a 60-year lease starting in 1948. It's now autumn 2007, 2 months from Reversion when the population of displaced European Jews and their descendents will be displaced again, this time by their American landlords. The novel apparently comes from the author having found a Yiddish travellers' phrase-book from the 1950s and imagined what kind of place it might be useful, and heard about a failed 1940s plan to resettle displaced European Jews in Alaska. Laced with ornately mournful humour, the book was reminiscent of Malcolm Pryce's Aberystwyth noir in its alternate history and almost surreal setting, though it seemed less tongue in cheek (then again, I've never been to Alaska or a Jewish enclave, so I could have missed the overtly silly parts).

Meyer Landsman, a middle-aged alcoholic detective who's falling apart at the seams, is nevertheless a sympathetic main character. I was rooting for him, I warmed to him, and I felt for him. First and foremost he is a policeman, and when Reversion comes the Sitka police force will be disbanded. What then? And what will happen to his neighbours, friends and family? There is an interesting theme of chess throughout the story - the ritual of playing it, the shame of not enjoying it when everyone else does, its puzzles as an allegory of life.

Chabon has written such lyrical prose that despite the relatively short chapters and the tension of the murder investigation (not to mention the headlong flight towards Reversion), I found myself putting the novel aside frequently to savour the images. At one point he described Landsman as walking 'with a kink in his back and an ache in his head and a sharp throbbing pain in his dignity'. It was a book that deserved to be read slowly.

Fans of the hard-boiled detective story might need to be patient with this novel, it's probably not as spare as they're used to. If you're not a detective fan, don't be put off - like the rugby in This Sporting Life it's a key part of the setting but not the only point to the story. I would recommend this widely to lovers of lyrical literature of wide open country, like The Shipping News by E Annie Proulx.