Over the years I had my Wordpress blog I wrote a fair few book reviews, most of which I’ve imported into my Substack archive, though I also reviewed for The Bookbag. Chances are you won’t have read them, and even if you did you may be in the mood now for a book you didn’t fancy then so I thought I’d collect a few together, with supplementary recommendations. For no particular reason I’m starting with crime and thrillers. Note that this post might be too long to display in full in an email, but you’ll see the rest if you click through to read it in a browser. If you make it all the way to the end, there’s one of my short stories waiting.

Set in Yorkshire

I’ll start close to home, with Kate Atkinson who is originally from Yorkshire, as is her series detective Jackson Brodie. I have long admired her writing, and in 2015 I wrote on my blog:

She has a natural, almost conversational style even when she’s sounding like Literature (with a capital L). She makes you care about the characters not because of their grand tragedy (though many of them do have tragic circumstances) but by details, little glimpses into their mildly disappointing childhood or a wholly inappropriate first love. With her tightly connected web and echoes of actions reverberating throughout the book, she manages to make even the most odd circumstances seem somehow plausible…she has a way of taking something ordinary, presenting it as magical, and thus emphasising its ordinariness. If only I could work out how she does it.

Atkinson is a big user of coincidences, which ought not to work but does. I have reviewed a few of her books but I think the only crime novel was Big Sky which is the most recent of her Jackson Brodie series and is set mainly at the Yorkshire coast. Brodie is a private detective who likes listening to female singer-songwriters and tends to have trouble with women, including his daughter, and has a tendency to stumble across answers rather than painstakingly working them out. Some of the books were made into a TV series called Case Histories, as I recall.

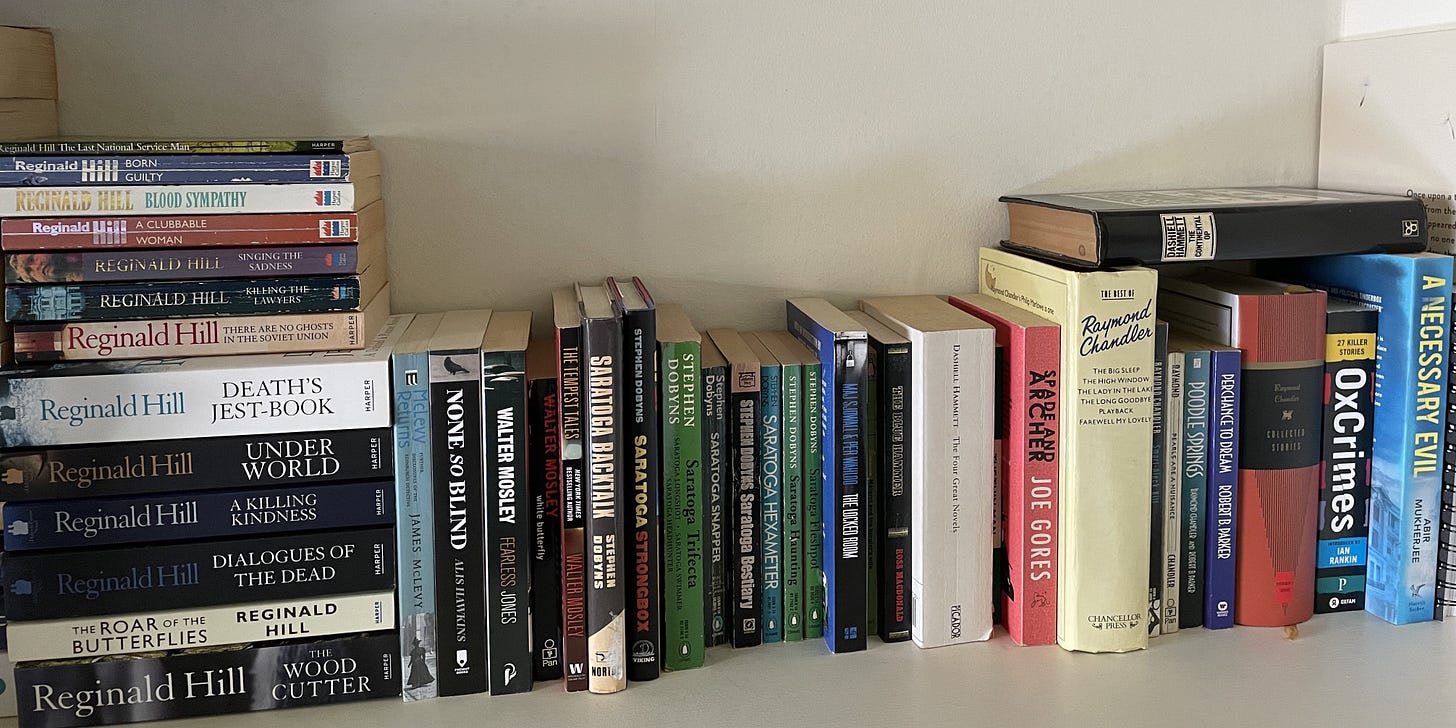

Reginald Hill was from elsewhere in the north of England but his most famous novels are set in Yorkshire, featuring police detectives Dalziel and Pascoe (also made into a TV series). He wrote them for about forty years, with the first one — A Clubbable Woman — published in 1970 and they changed in length and style over that time, from slim paperback Angry Young Man to long, complex, lyrical and occasionally with supernatural overtones.

Andy Dalziel might be an unrefined slob but he has sharp eyes and a sharper mind, and very little time for Peter Pascoe’s university-honed theories. Nevertheless there is a strong bond between them, and in 1994 Hill released a novella which gives us their first encounter — this appears to be the only Reginald Hill I reviewed. The Last National Service Man is not a conventional crime story — Dalziel has been taken hostage and dozy young Pascoe manages to join him — but it’s a good character study of the pair, perhaps best enjoyed once you’ve read a few of the novels.

European crime

Now to Europe, where like every other crime reader this century I sampled some Scandinavian authors a while back.

In Norway, Karin Fossum conjured the isolation and beauty of a village at the foot of a mountain in Don’t Look Back, the second in the Inspector Sejer series. In 2015 I said it was probably good for those who like their crime novels more thoughtful, like Ross Macdonald — we’ll come to him in a moment.

Over in Sweden Camilla Läckberg was inviting us to a small coastal town with its interconnectedness and gossip. I read the first two novels in the Patrik Hedström series: The Ice Princess and The Preacher, and noted that they had the natural humour of Dalziel and Pascoe and although ‘there are descriptions of gruesome situations, the books are by no means bloody and grim’.

Back in 2011 I picked up a Paris Noir anthology from Akashic Books, all translated from French and set in Paris. I found it grim and brutal on the whole, but 2 stories stood out. The Revenge of the Waiters by Jean-Bernard Pouy takes a theme I often play around with, that of the familiar stranger and particularly the way we notice their absences and wonder what’s become of them. With a welcome injection of dark humour, Pouy sets a band of bored waiters on an investigation into such an absence, with escalating consequences.

La Vie en Rose by Dominique Mainard makes good use of a technique that’s sometimes seen as old-fashioned, that of having our main character sit down and listen to a long and almost unbroken exposition of the back-story from the other main character. As an interesting twist, the listener is a proto-crime-writer pretending to be a private detective in order to gather material, but he soon finds he’s out of his depth.

You can’t do European crime writing without mentioning the pinnacle of Parisian detectives, Maigret, written by the Belgian author Georges Simenon. Perhaps you saw the Michael Gambon TV series in the 1990s, or the Rowan Atkinson one more recently — if not, both are well worth watching if you have access to them. I started reading the Maigret novels when I was barely out of primary school and my dad was doing a re-read from the local library. Like Reginald Hill, Simenon wrote his most famous novels over a period of about 40 years, from 1929.

I read 3 from the 1950s in 2021 (Maigret and the Man on the Bench, Maigret Takes a Room, and Maigret's Mistake) after a break of many years. I'd forgotten how gently melancholy they could be, as Maigret sits and ponders in cafes or his office, smoking his pipe. Rather than running around chasing people he seems to potter around Paris asking questions, slotting pieces of the puzzle together, occasionally sending his assistant Janvier off to track someone down. When they do corner the villain, Maigret is usually more disappointed than angry, particularly if they are young. I hadn't picked up on his underlying sadness at never having children, before, but it is mentioned in all three of those books I think.

I turned to Maigret as a comfort read during the post-lockdown uncertainty. They're not cosy crime, those three have sordid and grubby elements, hunger and desperation — no doubt the seamier side passed me by as a child. It's Maigret's attitude, his understanding, that makes them in any way comforting. In these days of paperback door-stoppers the Maigret novels are refreshingly short, a wet weekend read. There are 75 titles in the series, plus some short stories, so plenty to go at if you find you enjoy them.

USA, mostly hard-boiled

Everyone knows Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett — or at the very least the film versions of The Big Sleep and The Maltese Falcon — but have you heard of Ross Macdonald? Imagine if Raymond Chandler lost some of his terseness, lingering now and then to be thoughtful. Lew Archer is from a similar mould to Philip Marlowe, infused with jaded chivalry, and also works as a private eye in California. I reviewed two Ross Macdonald novels ten years apart; I’m lucky that the Library of Mum and Dad is well-stocked as I’m not sure they’re that easy to get hold of, but worth hunting down second-hand. The 18 Lew Archer novels were published from 1949-76.

In similar vein, Walter Mosley’s Easy Rawlins series is set in LA from the 1940s-60s. The differences here are that the series first appeared in the 1990s and is still going, and Easy Rawlins is a black private investigator and thus sees a whole other side to the underbelly of the city. I have read a few of the early ones and also Blood Grove which came out in 2021, and I prefer the earlier books — possibly for the simple reason that they’re set in Chandler’s time. I’ve also enjoyed some of Mosley’s other novels like Fearless Jones, but they are not in the same style.

I read Mr Mercedes by Stephen King in 2016 and noted that it was the only contemporary-set American novel I’d read recently, and it felt more foreign than the Scandinavian novels I’d been reading, with lots of unfamiliar cultural details. That said, I recommended it as easy to read and ‘up there with his best’, and advised readers: ‘If you’ve dismissed Stephen King as ‘just a horror writer’ but you like a good thriller or a tense detective novel, swallow your preconceptions and give Mr Mercedes a go. There’s less gore than in many a contemporary crime novel, and not the slightest hint of the supernatural...The characters felt like real people and the cranking of tension was spot on.’

Bill Hodges is a retired police detective, lonely and bored without the job that made up his entire adult life. Mr Mercedes is the one that got away, the last big case of Bill’s career. We as readers know his identity from the start — from the synopsis on the back cover, in fact — and we have to sit back and bite our nails as Bill Hodges is (unofficially) back on the case, hunting the guy down as he prepares to strike again. He’s not a policeman any more, he doesn’t even have a private detective licence, all he can do is use his brains and all those years of experience, and sail as close to the wind as he needs to.

India, mostly historical

Back in 2018 I read A Necessary Evil by Scottish author Abir Mukherjee. He was on a panel at the Penguin WriteNow insight day for writers from under-represented backgrounds that I was chosen for in 2017. I chatted to him a bit during that day, he seemed both thoughtful and entertaining, and I liked the sound of his crime series so I made sure I picked up one of the goodie bags that had his latest novel in it.

A Necessary Evil is set in India in 1920 and follows on from his debut A Rising Man, which I read and enjoyed a few months later; I don’t think I suffered too much by reading those two out of order. Captain Sam Wyndham of the Imperial Police, and his Sergeant Surendranath (‘Surrender-not’) Banerjee witness the assassination of the heir to the throne of one of the states they have no authority in. But he was assassinated within their jurisdiction, and Banerjee did go to school with him, so they go to his funeral, blunder into a political situation they don’t fully grasp, and race to find the truth.

Short chapters, flowing narrative voice with a dash of disrespectful humour, and a nicely flawed main character; I was hooked within a couple of pages and sped through it. Particularly good on complexity (characters and situations neither one obvious thing nor the other), and the British in India failing to — or refusing to — understand the culture they’re surrounded by, and being tripped up by preconceptions.

Vaseem Khan is another British author and a friend of Abir Mukherjee, in fact they are both part of the Red Hot Chili Writers podcast which interviews crime and mystery authors. I first came across his books in 2016 when I read his debut The Unexpected Inheritance of Inspector Chopra. Set in modern Mumbai, where I think Khan lived for a few years, it follows Inspector Chopra who has to retire from the police due to his health, and unexpectedly inherits a baby elephant. Naturally he sets up the Baby Ganesh detective agency.

I’ve also read the first 3 books in his more recent Malabar House series set in Bombay in 1950: Midnight at Malabar House, The Dying Day, The Lost Man of Bombay. I enjoy his style, readable and wryly amusing, and I like his protagonist Persis Wadia who is the only female detective in the Indian police. They’re very much cosy crime, puzzles in the style of Golden Age novels, but with a layer of the politics of post-partition India that gives them some bite. If you think you might enjoy his books I can recommend signing up to his newsletter, you get occasional short stories featuring his series characters, as well as extracts from forthcoming books and general chat about what he’s been up to, and books he’s enjoyed lately.

I hope you’ve found a book or author to explore. Let me know in the comments. I was going to include books which are a blend of SF and crime, but as this is already a long post I’ve decided to separate them out — look out for a review round-up on SF crime in a few weeks.

To round it all off here’s a link to a short story I wrote in 2017 about a writers’ retreat in the Highlands that goes horribly wrong.

She's working on a novel, she writes crime, maybe she's one of those crazy writers who approach the craft like a method actor. I grab for the gun, convinced now that it isn't loaded and getting sick of this childish play-acting. She's faster, and a spray of wood chips peppers the worktop.